Foreword

Devon is seen as a wonderful place to live, with many people being born in Devon, choosing to work here and live out their retirement in Devon. Such is Devon’s beauty and appeal it also attracts a lot of people from around the country to settle in Devon in later life. This movement of older adults into Devon goes some way to explain why Devon has an older population profile compared to most of the country. It is not just Devon though, we know across the country, rural and coastal areas are ageing at a faster rate than urban areas. With this of course comes many benefits with older people playing vital roles within their community and often providing caring support for their family and friends, however it can also bring some challenges when it comes to supporting older adults with health and care needs.

As the Chief Medical Officer points out in his most recent annual report (Chief Medical Officer’s Annual Report 2023 – Health in an Ageing Society) most people live well in their older age, seeing it as a time of great joy and happiness, free from illness and living independently. However, for some people older age it is a time of great difficulty, lacking independence, living with discomfort and poor health and loneliness. The difference between the two experiences is largely determined by health, both physical and mental health, and wellbeing. The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines healthy ageing as ‘developing and maintaining functional abilities that enables older people to enjoy a state of wellbeing’.

For the past 100 years we have used life expectancy as an indicator to tell us if we are getting healthier as a nation. Sir Michael Marmot in his 10-year review Michael Marmot Review published in 2020, identified that life expectancy in England over recent years has stalled so really the key data we need to look at now is ‘Healthy life expectancy’, the length of time you live free from illness and disease. While we would all hope to live a long life, we would wish that the amount of time we spend in poor health to be as short as possible. So, our attention now must be to move away from a focus on longevity to improving the quality of life and use this as an indicator of how healthy we are as a nation. Our ambition now must be to compress to a minimum, the number of years we spend in poor health.

My report this year highlights the changing demographic profile of Devon over the next twenty years and through modelling predicts future levels of illness and disability in Devon. The report not only provides a greater understanding of the future challenges we could face, but also provides an overview of what the evidence tells us we can do to enable people to maximise the number of years spent in good health, remaining active and living independently for as long as possible.

Steve Brown, Director of Public Health and Communities

Recommendations:

- Establish a workstream focused on developing predictive analytics to inform service planning across Public Health, Adult Social Care, Health and wider local authority services.

- Develop a dementia strategy to ensure there is an agreed and clear strategy for Devon.

- Increase targeted action on promoting people staying active physically, mentally and socially.

- Explore the adoption of Devon as a World Health Organization Age friendly community.

- Deliver on the Smoke-free generation ambitions and scale up our offer to support more smokers to quit.

- Work with key partners to increase action on the early identification and intervention of key health conditions, including high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, dementia, people at risk of falls.

- Support the national epidemiological survey on oral health in people aged 65yrs+ in care homes.

- Maintaining high attendance at national screening and uptake of national immunisation programmes.

- Equality impact assessments should be undertaken on all policy decisions to ensure that proposed actions are proportionately targeted at the most deprived communities to tackle health inequalities.

1. Understanding the demographic change in Devon

Devon has an older population profile and faster population growth than the national average. This population change, coupled with the fact that people are spending more years in ill-health, poses challenges in Devon in relation to the health, wellbeing and quality of life of Devon’s citizens.

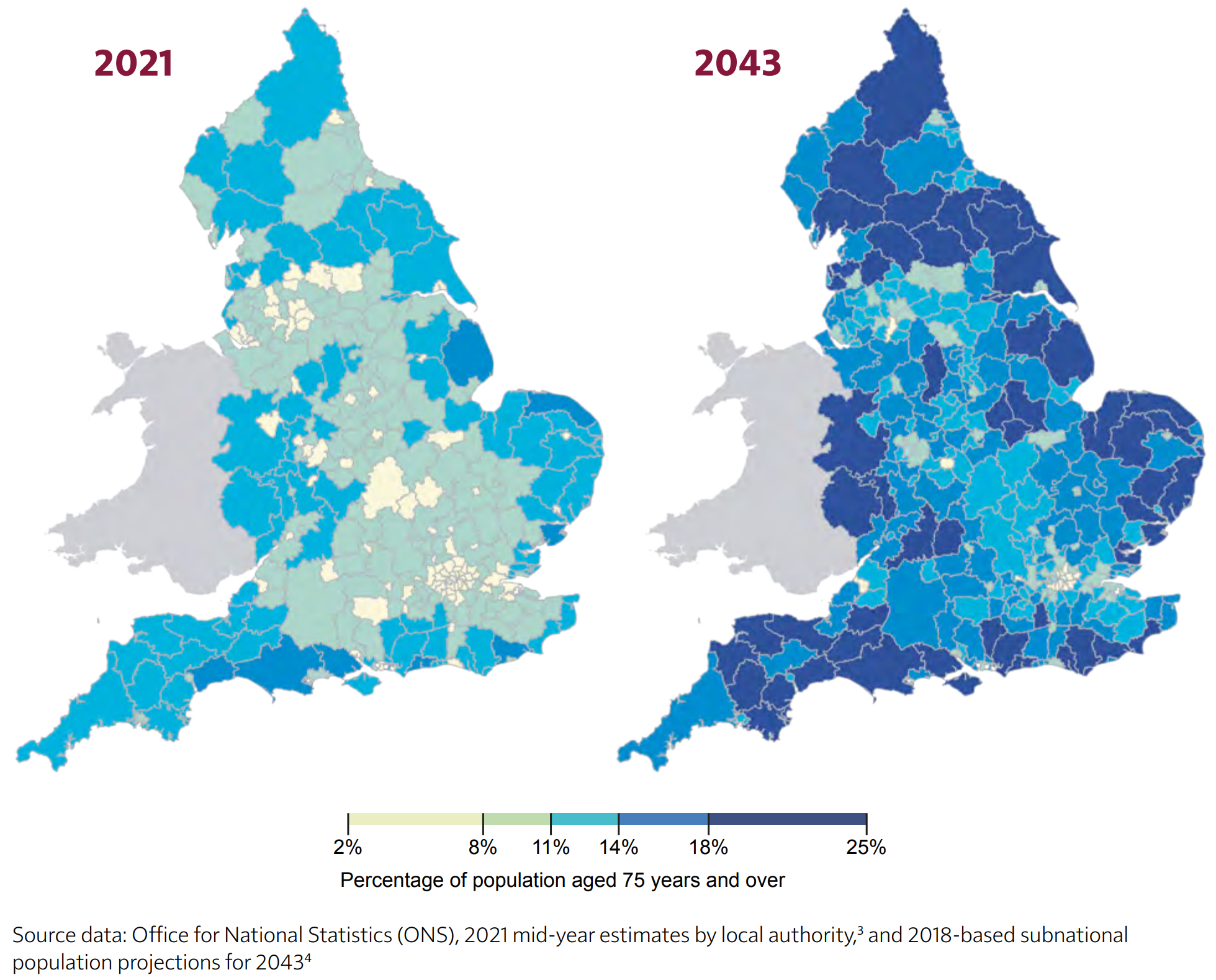

The map presented in Figure 1.1 shows the projected rise in the percentage of population aged 75 years and older. It clearly shows that it is the coastal and rural areas which are ageing faster. The impact on Devon is clear with the predicted proportion of those aged 75 and over living in Devon increasing from 13.7% in 2024 to 18.4% in 2043.

Figure 1.1: Map of England showing the projected rise in the percentage of the population aged 75 years and over

Image Source: Chief Medical Officer’s Report, 2023

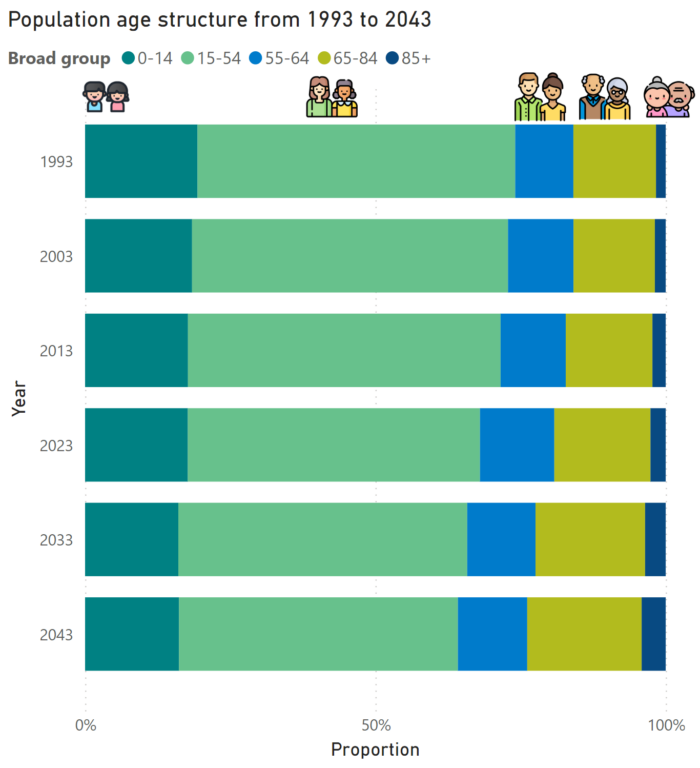

While Devon will experience an increase in older adults (65 years +) over the coming decades, with number of older adults rising from 225,000 to 301,000 by 2043 it will also see a reduction proportionately, in the younger and working age groups. Figure 1.2 shows the change in the population profile from 1993 through to 2043.

Figure 1.2: Change in Devon population structure from 1993 to 2043

Source: APHR Dashboard. Data from Office for National Statistics Mid-Year Population estimates (1993-2013) and sub-national population projections (2023-2043)

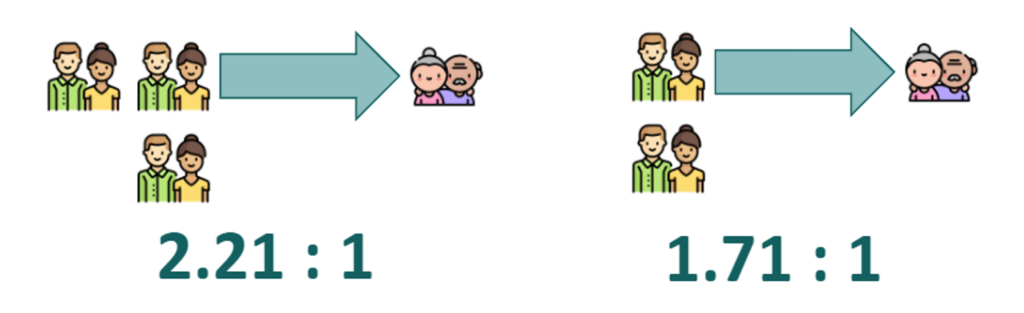

With reductions in births in the future, together with a growing ageing population, the ratio of younger people to older people will also reduce. This inevitably will impact on our frontline workforce including carers, both paid and unpaid. Currently across Devon, there are just over 2 working-age people to one older person. By 2043, we expect this to reduce to 1.7 working-age people (figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3: Comparing dependency ratio for 2023 and 2043

Source: APHR Dashboard. Data from Office for National Statistics Sub-national population projections (2023-2043)

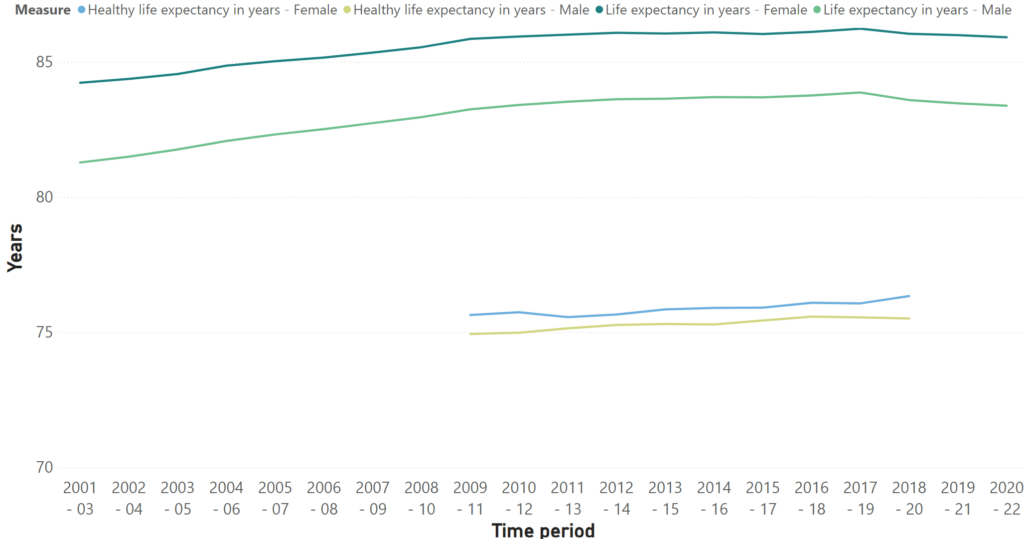

Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy are useful measures to understand the health our population. Over the past decade, life expectancy has stalled and remained similar both locally and nationally. The average life expectancy across Devon is 85 and 87 years with average healthy life expectancy being approximately 77 and 79 years (male and female respectively). This indicates that people in Devon are on average living around a decade in poorer health (Figure 1.4). As with life expectancy, no significant improvement in healthy life expectancy has been seen over the last decade.

Figure 1.4: Change in Devon health and life expectancy at 65 years (3 years pooled 2001-2003 to 2020-2022)

Source: APHR Dashboard. Data from Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, Public Health Outcomes Framework, 2024

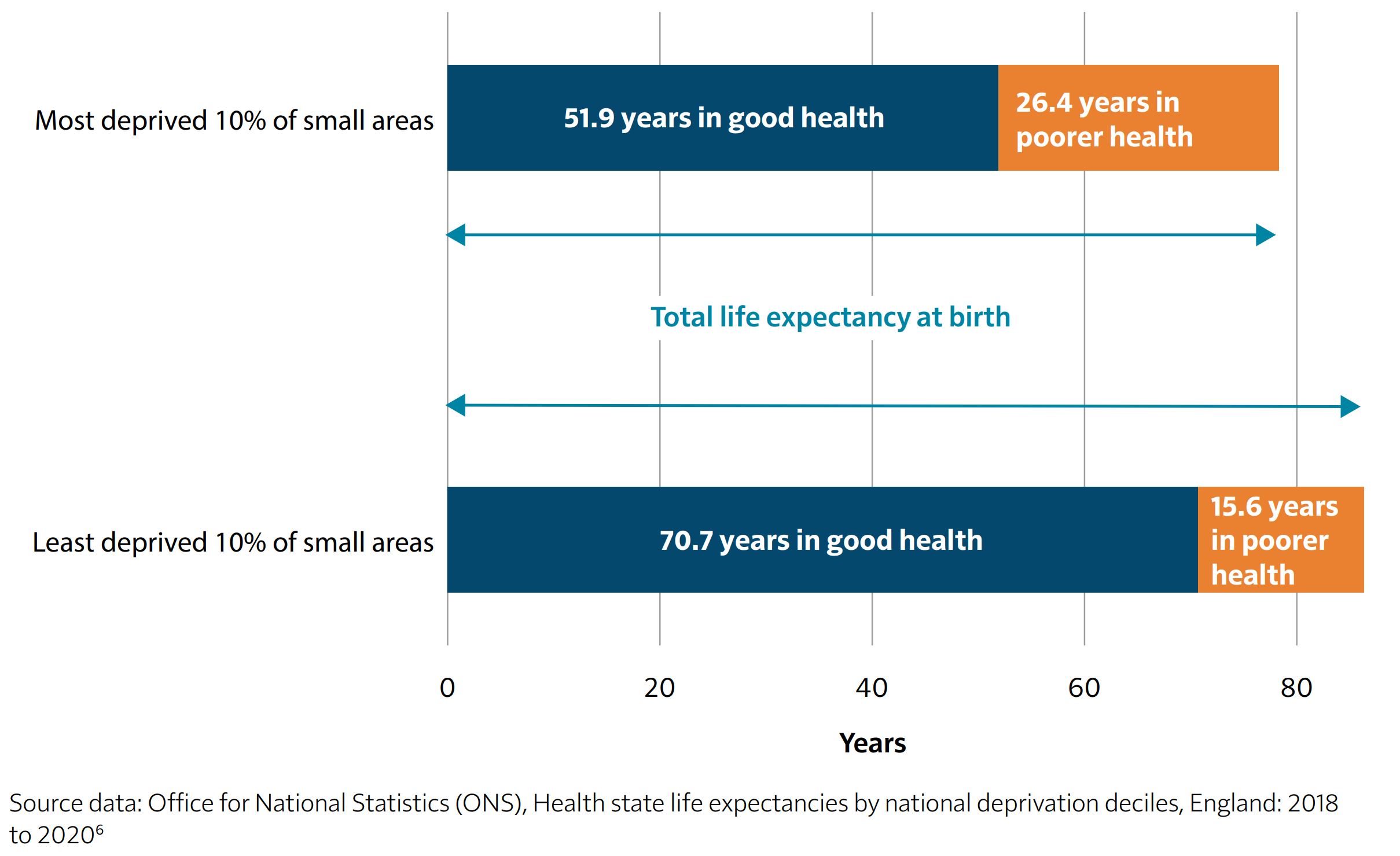

Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy are not equally distributed amongst society. Figure 1.5 uses data for England to shows the stark variation for females in both life expectancy and healthy life expectancy. The chart shows a strong link between deprivation and the proportion, and absolute periods spent living in poorer health. Females living in the most deprived 10% areas not only have a shorter life expectancy, compared to the most affluent 10%, but also spend around a third of their life living in poorer health. This clearly demonstrates the health inequalities which exists and the need to ensure interventions are targeted at those in greatest need.

Figure 1.5: Inequality in life expectancy and healthy life expectancy at birth for females in the most and least deprived areas in England, 2018 to 2020

Image Source: Chief Medical Officer’s Report, 2023

2. Understanding health in an ageing Devon

Whilst for some there are clearly health challenges and conditions associated with ageing, it is important to note that many people enter older age, and remain, in good health. For example, most people (90%) in their 80s do not have Dementia and only 4% live in a care home.

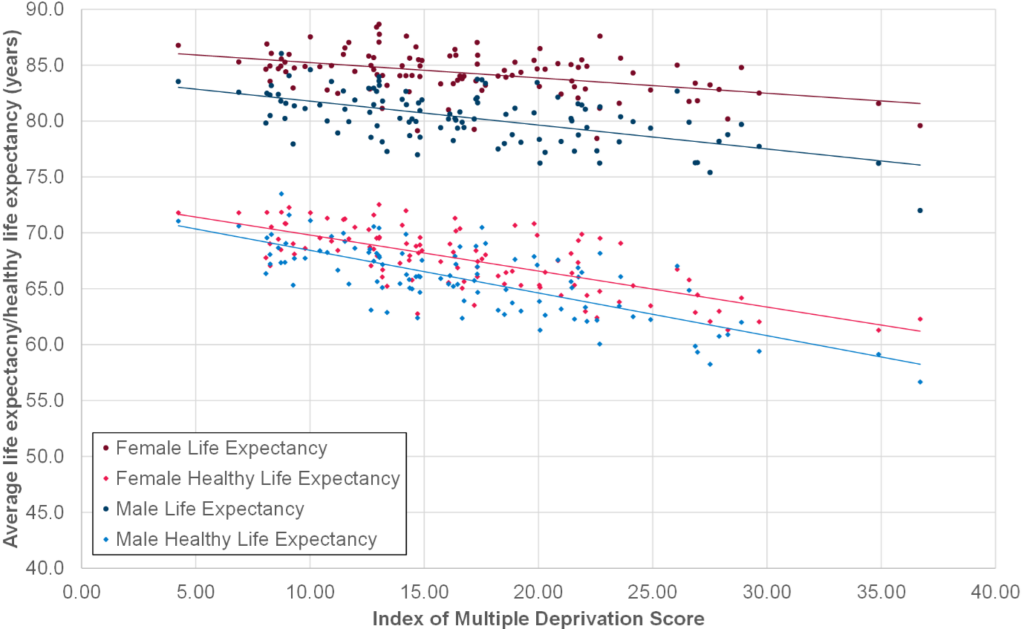

How long people live, and the proportion of this time spent in good health is determined by a complex mix of non-modifiable and modifiable factors. This is reflected in the differences in life expectancy and health life expectancy across Devon where income, housing and employment, lifestyles and access to health care and other services can be very different depending on where you live. Across Devon there is a 15-year gap in life expectancy and a 20-year gap in healthy life expectancy between the highest and lowest communities across the wider Devon area, with areas with higher levels of deprivation such as Ilfracombe, Central Exeter, and Central Barnstaple amongst the lowest (figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Health and Life Expectancies and Index of Multiple Deprivation Score by Devon Middle Super Output Area, 2009-2013

Source: Office for National Statistics 2009-13, and Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 2019

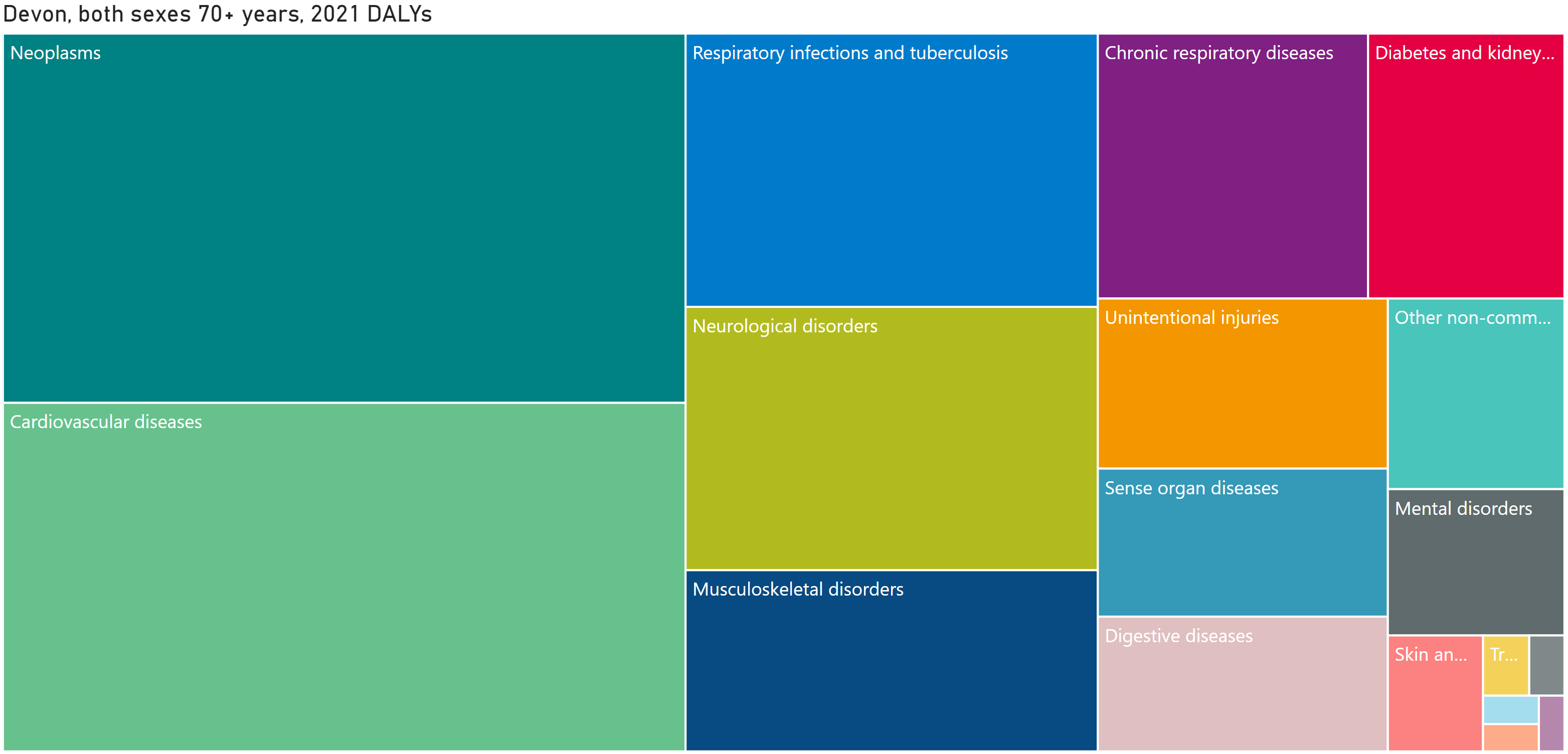

The global burden of disease chart (figure 2.2) shows that cardiovascular disease, neoplasms (cancer), mental disorders, diabetes and chronic kidney disease are amongst the leading causes of life lost to ill health, disability or early death in people over 70 years in Devon. Whilst diseases, long term conditions, and disabilities are more common in older people, the risk of developing these conditions can be reduced and indeed slowed by preventative measures.

Figure 2.2: Global burden of disease for Devon in adults aged over 70 years

Source: APHR Dashboard. Data from Global Burden of Disease, 2021

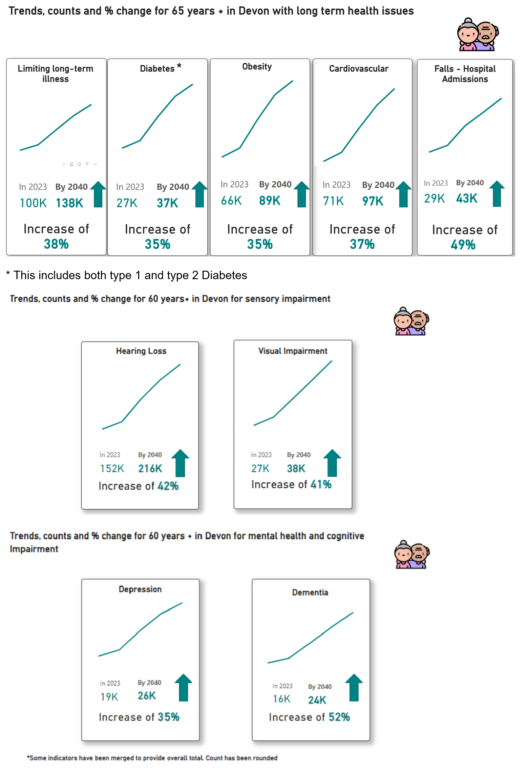

Across Devon rates of dementia, degenerative diseases and frailty are continuing to rise and predicted to grow by 45% by 2040.

The dementia diagnosis across Devon continues to be below target levels set out through NHS mandate with an ambition to increase dementia diagnosis rates both nationally and locally. In Devon the current dementia diagnosis rate is 55.6% representing almost 1 in 2 people that are undiagnosed with dementia. This presents significant opportunities to improve diagnosis rates, health and wellbeing outcomes, and the impact across the health and social care system for those who are undiagnosed without care and support. There is a considerable economic cost associated with this disease which is predicted to triple by 2040. This is greater than the cost of Cancer, Heart Disease and Stroke (Dementia, NHS England, 2023).

Figure 2.3: Predicted growth in selected long-term conditions and disabilities, Devon, 2019 to 2040

Source: Projecting Older People Population Information System (POPPI), 2024

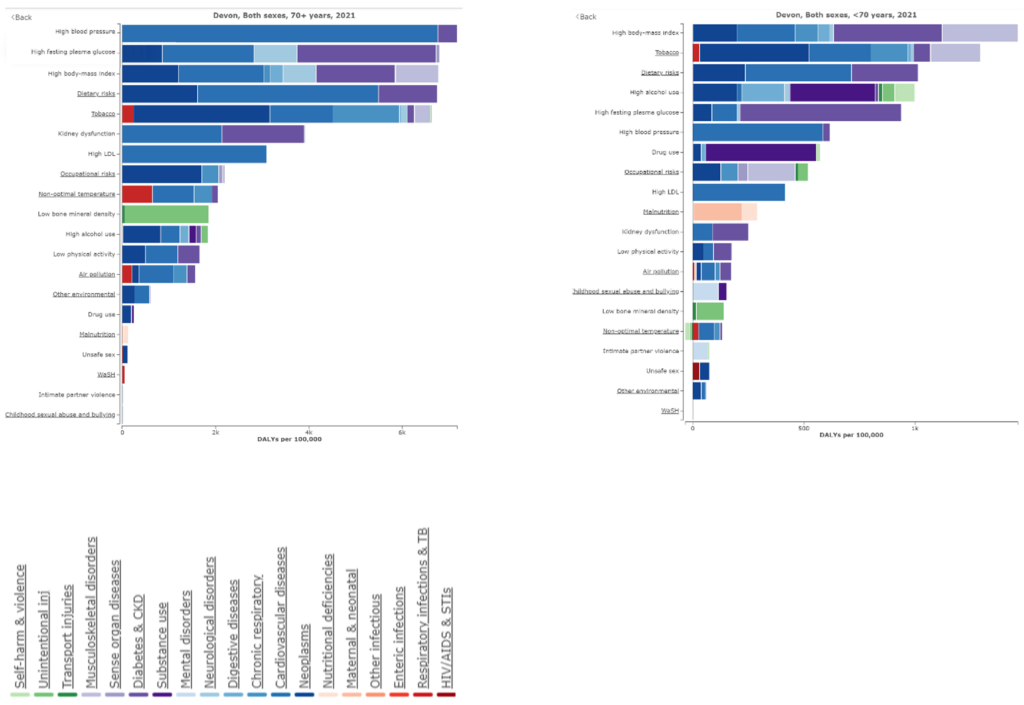

Figure 2.4 shows that the main leading risk factors causing life lost to ill health, disability or early death in people over 70 years in Devon include high blood pressure, diabetes (type 1 & type 2), high BMI, dietary risks and smoking. These risks factors are similar to the leading risk factors for those under 70 years in Devon albeit a different order. The distinction is important because what this shows us is that we observe more downstream outcome risk factors at 70+ which are greatly influenced by the top leading risk factors in those under 70 years. As such, if we make efforts to improve physical activity, smoking, diet and alcohol through the life course, the risk of developing certain diseases, long term conditions, and disabilities later on in life can be reduced and indeed slowed for the Devon population to ‘age well’.

Figure 2.4: Risk Factors across Devon for 70+ and <70 Years (DALYs per 100,000, both sexes, 2021)

Source: Global Burden of Disease, 2021

For more data, please visit the Ageing Well Annual Public Health Report Dashboard: APHR Dashboard.

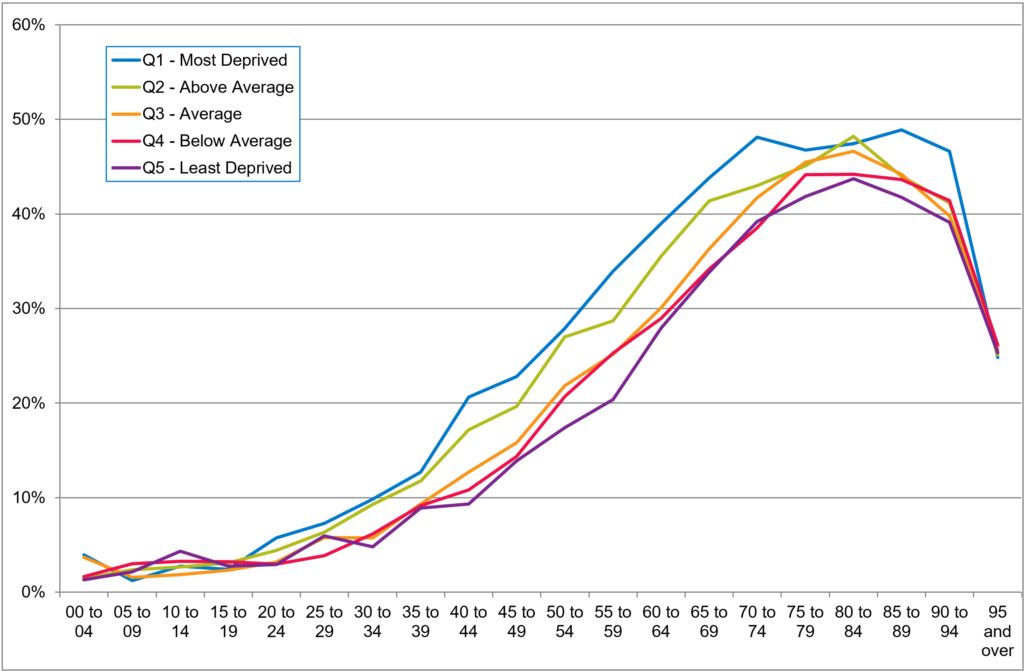

Multi-morbidity refers to the coexistence of two or more long-term conditions in the same individual, including defined physical and mental conditions, disability and sensory impairment. According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Prevalence | Background information | Multimorbidity | CKS | NICE), around 42.4% of people across all age groups experience multi-morbidity, increasing from 28.0% in under 59 year olds, 47.6% in 59 to 73 year olds, and 67.0% in those aged 74 and over. Given population projections and ageing in Devon the number and percentage of people with multi-morbidity will increase significantly over the next 20 years. This is further expanded in figure 2.5, which uses a measure of complex multi-morbidity (five or more comorbidities) for emergency admissions to hospital in Devon. This highlights that not only does multi-morbidity increases with age but is also higher and has an earlier onset in more deprived areas. This accords with the 15-20 year gap in health expectancies, with complex health problems tending to have an onset much earlier in more deprived communities. It is also interesting that after the age of 90 the proportion actually drops, which also reflects longer life expectancy for those without complex health problems.

Figure 2.5: Percentage of emergency admissions with five or move comorbidities by age and deprivation, Devon

Source: Devon Long-Term Conditions Health Needs Assessment, 2015

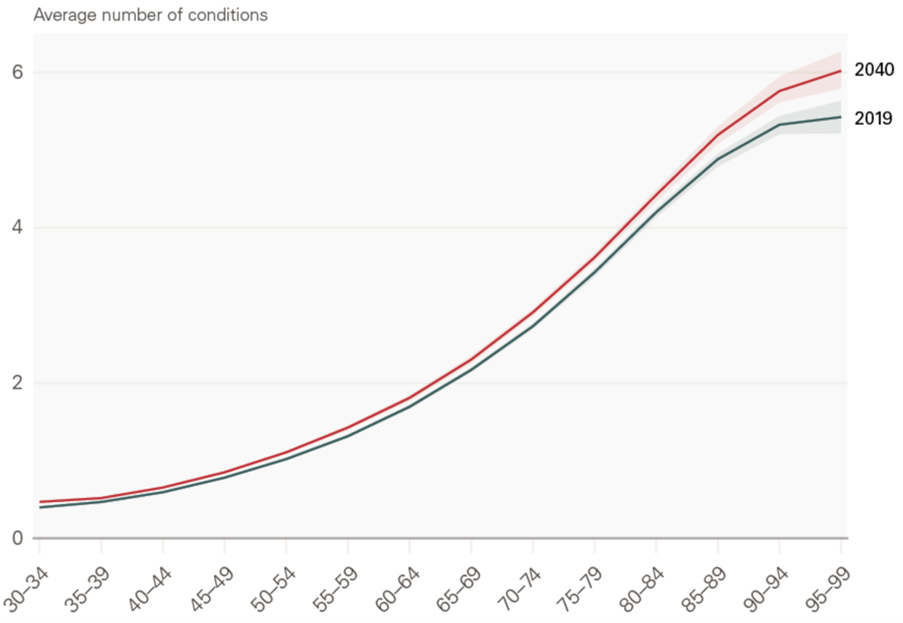

In 2023 the Health Foundation published the report ‘Health in 2040: projected patterns of illness in England’, which highlighted that the amount of time that people are projected to live with major illness is expected to increase from 11.2 years in 2019 to 12.6 years in 2040. The number of adults in England living with a major illness is projected to rise from 1 in 6 in 2019 (6.7 million) to 1 in 5 in 2040 (9.1 million). Whilst this increase is in part driven by population growth and ageing, the report also highlighted that part of this growth is also driven by increasing levels of prevalence at all ages, driven particularly by lifestyle factors, which is particularly reflected in conditions such as Diabetes and Cardiovascular disease. This is reflected in figure 2.6, which predicts that over the next two decades the average number of conditions will increase in all age groups and the growth will be more rapid in older age groups.

Figure 2.6: Average number of Cambridge Multimorbidity score conditions by five year age groups in persons aged 30 plus in England, 2019 and 2024

Source: The Health Foundation – Health in 2040: projected patterns of illness in England, 2023

Reflections

The data is clear that as we see a rise in the number of older adults in Devon over the coming years, we are going to see an increase in the number of people living with long-term conditions, disease and disability. Ultimately the scale of the challenge associated with an increase in older adults living in poor health will depend upon the actions taken now to increase our healthy life expectancy and compress the number of years spent in poor health. The data also highlights a worrying decrease in the proportion of working age adults and older people which inevitably will have implications for health and care workforce as well as unpaid carers as we try and respond and support an increase in health and care need in Devon.

Recommendations

1. Establish a workstream focused on developing predictive analytics to inform service planning across Public Health, Adult Social Care, Health and wider local authority services.

2. Develop a dementia strategy to ensure there is an agreed and clear strategy for Devon.

3. Promoting and improving health in later life

As we age, we know that disability, disease, and long-term conditions become more common, however we should not consider this as an inevitable part of ageing. There are actions we can take as individuals, families, communities and as a wider health and care system to promote healthy ageing, reducing the risk of degenerative disease, dementia and frailty and enable people as they get older to continue to live independently, healthy and active lives for as long as possible.

It is important to ensure that the advice, guidance, and the interventions promoted are going to have a positive impact and thus need to be evidence-based. So, to understand what the most effective solutions are to prevent, delay or reduce ill health, thus increasing healthy life expectancy public health has undertaken a rapid review of the published evidence. This section provides an overview of this review Public Health Devon – A Rapid Review of the Evidence for Ageing Well, April 2024 detailing the evidence-based interventions which will have the greatest impact on bringing about improvements to health and wellbeing across the life course.

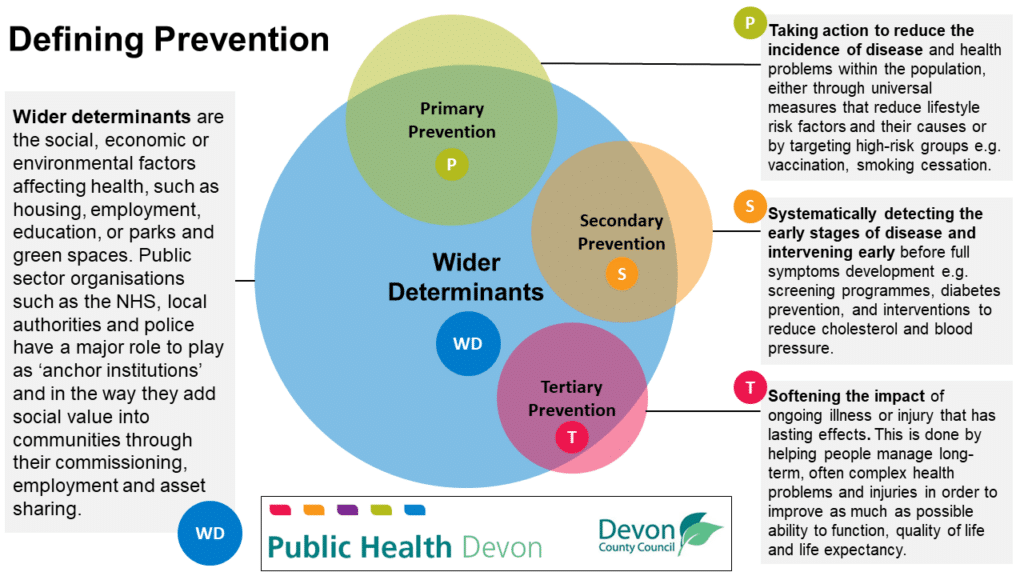

When we consider preventative interventions, it is important there is clear understanding of what we mean by prevention. My annual report last year (Annual Public Health Report 2022-23 – Devon Health and Wellbeing) was dedicated to understanding the various components to prevention which are captured in figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Defining prevention

Source: Public Health, Devon County Council, 2023

There is a complex relationship and contribution of primary, secondary and tertiary prevention measures, alongside action on wider determinants of health, towards improvements in health, wellbeing and quality of life. The reality is in adopting a preventative approach, action is required in all four elements of prevention.

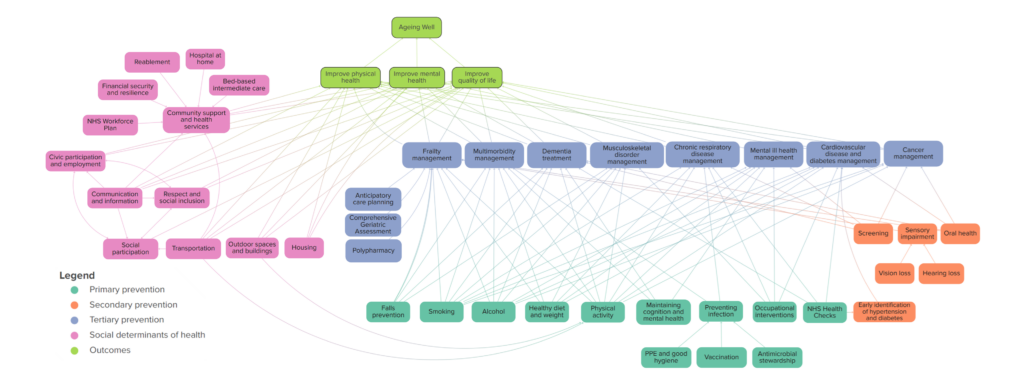

As part of the rapid evidence review a theory of change model was developed which maps out the contribution of preventative measures and actions on key wider determinants of health toward ageing well. The theory of change diagram in Figure 3.2 highlights the inter relationships between all four prevention approaches has on healthy ageing.

Figure 3.2: Ageing well theory of change

Source: Public Health Devon – A Rapid Review of the Evidence for Ageing Well, April 2024

The evidence review examined the published literature in relation to healthy ageing and an assessment and grading of the quality of available evidence for effectiveness and cost-effectiveness was made. Some areas of research are more established than others and an absence of high-quality evidence does not necessarily mean an intervention is not effective. The evidence base for most primary and tertiary prevention measures are well established, as can be seen in the theory of change model in Figure 3.2. However, some interventions are less well represented in the literature, such as measures to tackle wider determinants of health for ageing well.

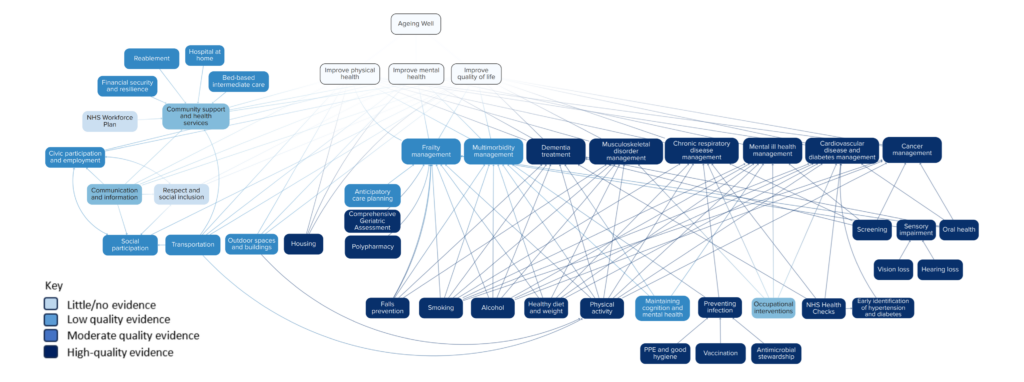

Each intervention was assessed for its strength of evidence and mapped against the theory of change for ageing well through action on prevention and wider social determinants of health. The outcome of this is represented in figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3: Ageing well theory of change strength of evidence model

Source: Public Health Devon – A Rapid Review of the Evidence for Ageing Well, April 2024

When looking to understand what actions and interventions we should be focusing on to give us the best chance of staying healthy for as long as possible it is vital that we take an evidence-based approach. Understanding what the global research tells us about what actions make the largest contributions to preventing, delaying or minimising disability and frailty is vital. The following section provides an overview of the high-quality evidence interventions which have been proven to be effective and cost effective.

Staying active!

Staying active physically, mentally and socially are important things we can do to support the population of Devon to age well. It is never too early or indeed too late to start, and the evidence is clear, action at any stage of life can support us to live happier and healthier in older age.

Figure 3.4: Staying active recommendations

Original Photo Source: Photo by Centre for Ageing Better on Unsplash

Being physically active

Physical activity is a key protective factor for ageing well and has been proven to reduce your risk of early death by up to 30%. Preserving musculoskeletal function through physical activity and exercise is a necessary requirement for maintaining mobility and independent living during later life. Older adults can experience balance problems and muscle weakness and impaired balance are significant risk factors for falls.

People who exercise regularly have a lower risk of developing many chronic conditions, such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, and some cancers. Physical activity can also boost self-esteem, mood, sleep quality and energy, as well as reducing risk of stress, clinical depression and dementia.

However, the proportion of people who are physically inactive increases sharply with age. Rather than being considered as an inevitable effect of ageing, increasing physical activity at any age can instead prevent or reverse deconditioning, supporting people to participate in the activities they enjoy and improve health and wellbeing. The good news is that no matter what age we are, or how many health conditions we have, the gap between our current level of activity and our best possible level of activity can be reduced, so that we can all live better for longer.

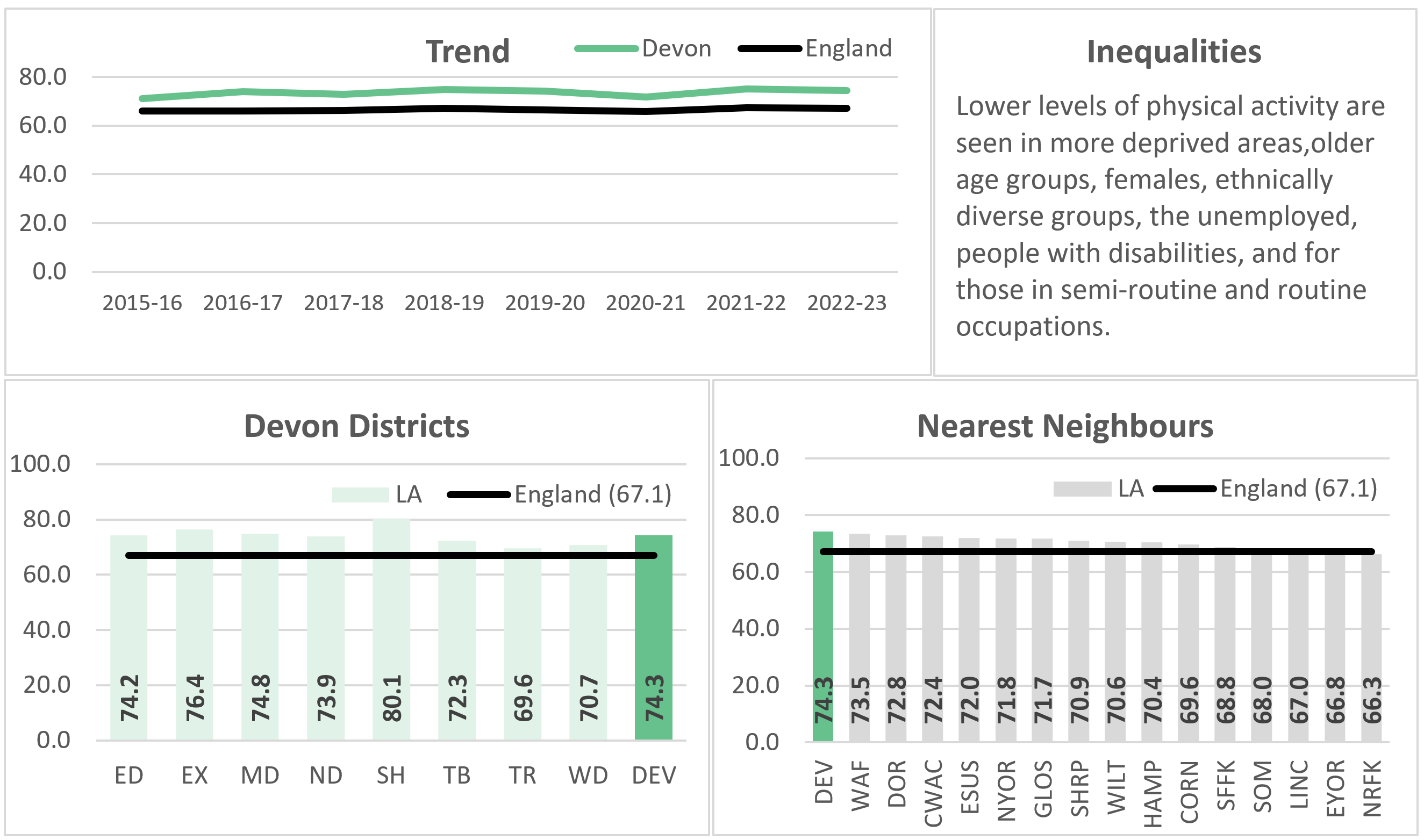

The UK Chief Medical Officers’ physical activity guidelines recommend that older adults should aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity physical activity per week. The guidelines also recommend individuals to undertake activities aimed at improving muscle strength and balance on at least 2 non-consecutive days per week. The latest data (2022-23) shows that 74.3% of the adult population in Devon are meeting physical activity recommendations, which is above the national average (67.1%), and highest amongst local authorities similar to Devon (nearest neighbour group). It is important to note however that significant differences exist within the population with lower rates particularly evidence in more deprived rural areas of Devon, and lower activity levels particularly seen in more deprived areas, older age groups, females, ethnically diverse groups and those with disabilities.

Figure 3.5: Physical Activity in Devon: Trends, Inequalities and Benchmarking, 2022-23

Source: Active Lives Survey and Public Health Outcomes Framework, 2024

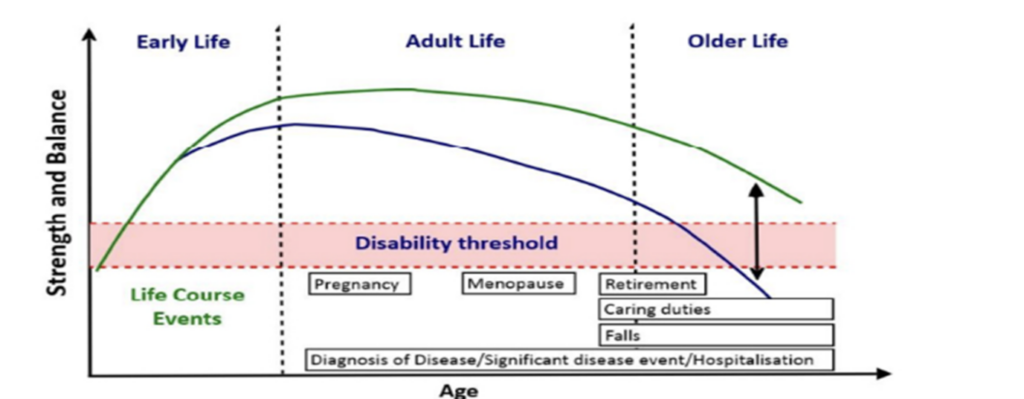

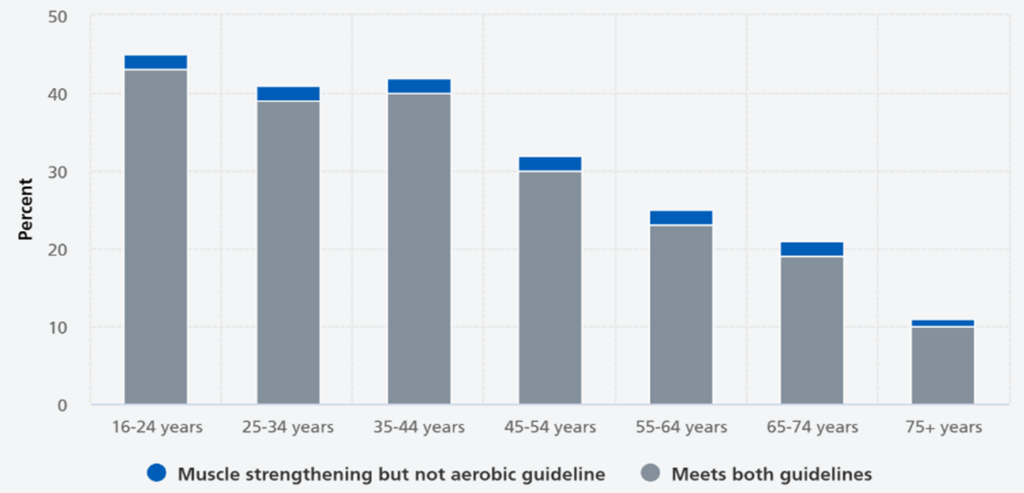

Physical activity is particularly important for maintaining function and reducing frailty in older age, with aerobic activity to boost the cardio-vascular system, and muscle strengthening activities at least twice a week to increase bone strength and muscular fitness. Figure 3.6 shows the importance of preserving strength and balance over the life course. However, according to the Health Survey for England (figure 3.7) the majority of working age adults do not meet these guidelines, and only one in five aged 65 to 74, and one in ten aged 75 and over, do. Females and those living in more deprived areas are also less likely to meet the Chief Medical Officer guidelines.

Figure 3.6: Importance of physical activity to preserve strength and balance ability over the life course

Source: Skelton DA, Mavroeidi A (2018) ‘How do muscle and bone strengthening and balance activities (MBSBA) vary across the life course and are there particular ages where MBSBA are important’. Journal of Frailty. Sarcopenia and Falls 3(2): 74-84

Figure 3.7: Proportion meeting aerobic and muscle strengthening guidelines by age, England, 2021

Source: Health Survey for England, 2021

Case Study: The Connecting Actively To Nature Programme (CAN)

This programme is managed by Active Devon using funding from Sport England and supported by the Devon Local Nature Partnership. It was initially a five-year programme targeting individuals aged 55+ who are experiencing changing family structures, isolation, retirement and/or increased caring responsibilities and helps them to discover the combined physical and psychological benefits of activity in nature. The programme sought to provide opportunities for people who were taking their first steps into activity. Working with local and community partners, the activity offered was a varied mix including nature walks, arts in nature, wild swimming and beginner running groups, among others, developed with local partners to meet the local need/interest.

The main aim was to improve existing groups and activities so that they better met the needs of inactive people and/ or to establish new offers where there was a lack of opportunity for local people. 2,827 people aged 55+ took part in a CAN project, with more than 60 delivery partners engaged in delivering or supporting the programme, delivering more than 200 projects.

Chill Sea session in Northern Devon

Staying mentally active

Promoting and protecting mental health is vital to improve quality of life and is associated with better physical health. This includes better heart health, an improvement in the ability of our immune systems to fight infections and slower progression of other health conditions. Having good mental health and wellbeing also supports people’s ability to fulfil their ambitions, to be more confident, have good relationships with other people and to improve resilience. Better mental health and wellbeing may also improve community spirit, bringing people together and reducing levels of violence, intolerance and crime.

Poor mental health in older age is not inevitable and mental health conditions can often be prevented or treated. However, depression and other mental health conditions in older people often go underdiagnosed and undertreated. It is important to break the stigma of talking about mental health and to support measures to improve early identification and treatment of mental health problems.

Evidence supports interventions which promote social interaction, such as volunteering or enhancing community engagement, to improve wellbeing and reduce depression. Furthermore, there is strong evidence that physical activity prevents, reduces or delays depression and anxiety.

Case Study: Seachange

Seachange is a charity which provides an inspiring new approach to community support. Working on the basis that good health and happiness are closely linked, offering easy access to practical support for all generations, young and old, within its area of Exmouth, Woodbury and Budleigh Salterton.

Their programme of events is all designed to increase social cohesiveness, reduce isolation, and loneliness whilst improving the health and happiness of our community. They also support other community organisations, such as Launchpad, who provide training for adults with learning challenges in catering and hospitality.

Photo from community event at Seachange Budleigh Health Hub

Photo courtesy of Launchpad

Remaining socially active

Participating in leisure, cultural and spiritual activities in the community is important for health and wellbeing, a sense of belonging and good relationships. Without social participation, people can experience loneliness and isolation. Although linked, loneliness and social isolation are not the same. People can be isolated yet not feel lonely, equally they can be surrounded by others and feel lonely.

While loneliness and social isolation can affect all ages, older people are especially vulnerable. Being lonely or isolated can lead to deterioration in health and wellbeing and is a symptom of common mental health conditions. Characteristics and circumstances associated with a higher likelihood of loneliness included being female, being single or widowed, being in poor health, being in rented accommodation and having a weak sense of belonging to a neighbourhood. Deprivation is also strongly associated with loneliness, with those living in more deprived areas more likely to experience it.

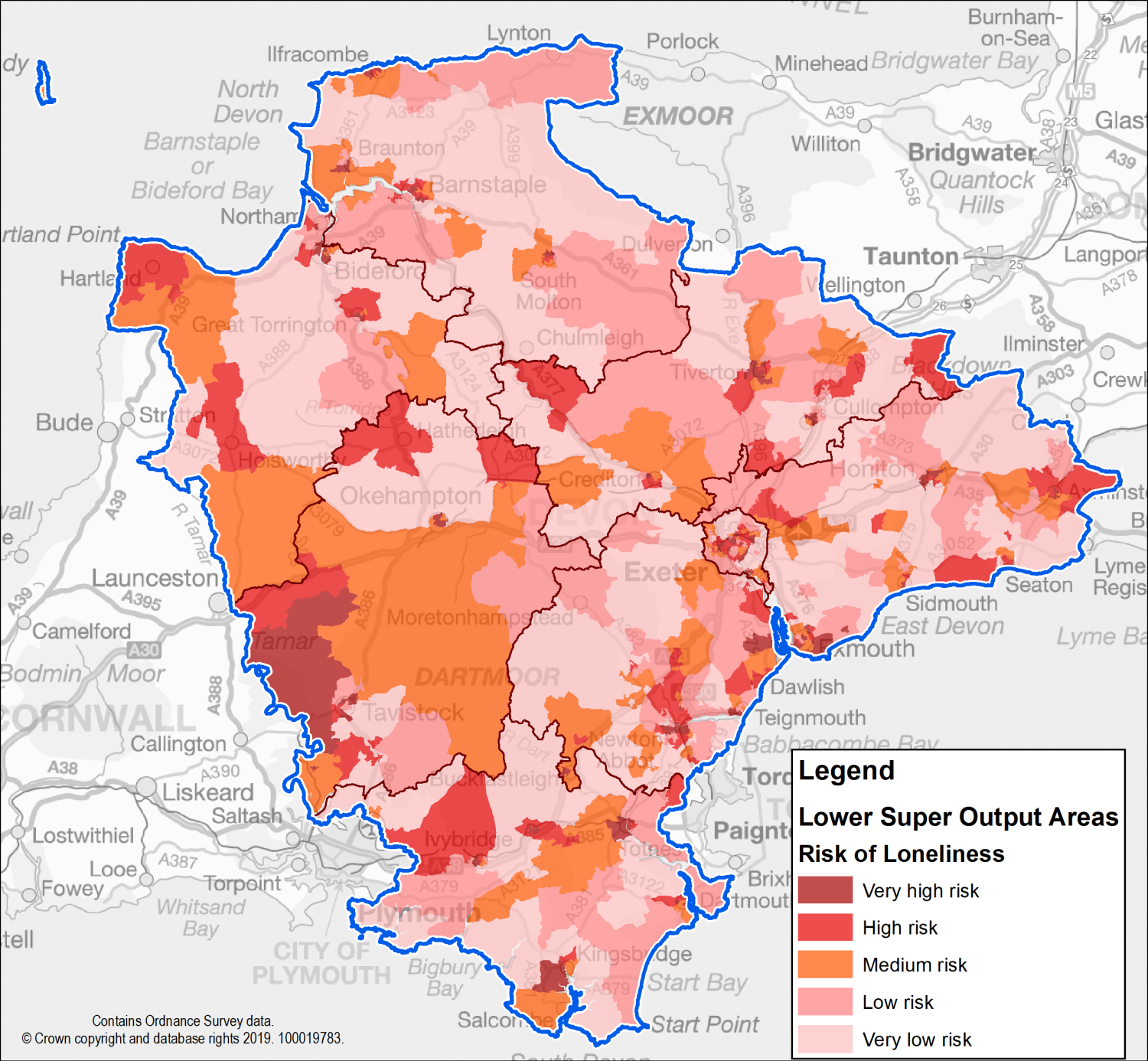

Age UK produce a loneliness risk map which assigns neighbourhoods to five risk categories based on the social and demographic composition of the area.

Figure 3.8: Loneliness heat map for Devon

Source: Age UK Loneliness Risk Map and Devon County Council, 2019

In Devon, as illustrated in Figure 3.8, neighbourhoods at very high risk or high risk of loneliness are seen in all local authority districts. Very high-risk communities are seen in the city of Exeter and market and coastal towns across the county, with higher loneliness risk associated with socio-economic deprivation. Whilst rural areas typically have a lower risk of loneliness than urban areas, very high risk or high-risk rural communities are still evident, particularly in West Devon, Torridge and Mid Devon. This is associated with higher levels of deprivation in rural communities linked to lower incomes and access.

Loneliness has a considerable impact on health and wellbeing, with lonely individuals having a greater risk of ill-health and a lower quality of life. Lonely people are more likely to develop dementia and depression, and through living less-active lives will also be at increased risk of experiencing type 2 diabetes, stroke, heart disease and disability. A lack of social support structures also makes individuals more like to use health services and enter care. According to research by the World Health Organisation, both increase the risks of cardiovascular disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, cognitive decline, dementia, depression, anxiety, and suicide. They also shorten life expectancy and reduce quality of life.

Core prevention activities

There is a strong evidence base for continued system wide focus and support on delivering a smoke-free generation and supporting individuals to quit smoking, alongside ensuring high attendance at national screening and immunisation programmes. Efforts to improve early identification of key health and wellbeing conditions, including high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes, declining oral health, and people at risk of falls, through measures such as proactive case identification and ensuring all eligible individuals receive their NHS Health Check are important for supporting the population of Devon to age well. However, further action could be taken to improve and maintain implementation effectiveness with respect to the reach and uptake of these interventions, particularly within areas of deprivation and minority groups.

Figure 3.9: Core prevention strategies

Image Source: Unsplash

Hypertension and high cholesterol case finding

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) can have a significant impact on the lives of older people, making daily activities challenging and reducing independence. It is the largest contributor to disability adjusted life years and a major driver of health inequalities. Poor cardiovascular health can lead to a number of major conditions more common in older age, including heart attacks, strokes, heart failure, chronic kidney disease and vascular dementia.

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the most common form of CVD in England and is increasingly likely to develop as people get older. Secondary prevention interventions, such as medications to lower blood pressure, decrease cholesterol levels and prevent blood clots can work rapidly and effectively to reduce the risk of a serious CVD event. Preventing serious CVD events reduces the likelihood of someone being admitted to hospital and having to undergo cardiac interventions or stroke rehabilitation, both of which have potential long-lasting impacts on health, quality of life and independence.

Hypertension case-finding and optimal hypertension and lipid management is one of the five key clinical areas of health inequities highlighted in the NHS CORE20PLUS5.

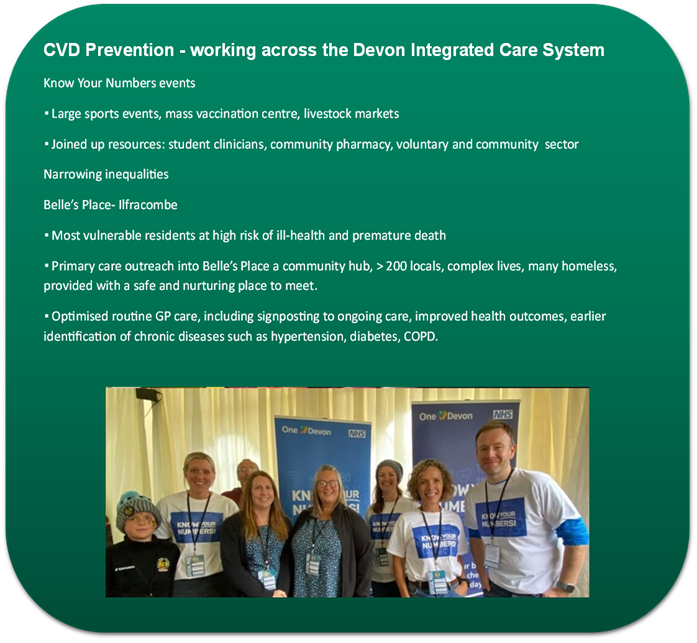

Case Study: CVD Prevention (Devon Integrated Care System)

Public Health Devon is working with the NHS, the Voluntary and Community Social Enterprise (CVSE) sector and community groups to help identify undiagnosed high blood pressure in adults in Devon.

Blood pressure monitoring in community pharmacy settings, followed by home based monitoring, is a high impact intervention to reduce the impact of cardiovascular disease, with the potential to increase the identification of hypertension, reduce the burden on health services and promoting healthier behaviours, saving both the NHS and local authorities money. Furthermore, high cholesterol identification and risk stratification has also been identified as a low-cost intervention, adaptable to local systems, with the potential to save lives, reduce hospital admissions and cut costs.

NHS Health Checks

The NHS Health Check is an opportunity to measure and manage cardiovascular disease risk for individuals between the ages of 40 and 74 years and not on a disease register. It can support individuals to adopt healthier behaviour, to access support services and identify a need to prescribe medication such as statins.

Through the health check, the risk of having a heart attack or stroke in the next ten years and of developing type 2 diabetes is calculated. Underpinning this is an assessment of six major risk factors that drive early death, disability, and health inequality: alcohol intake, cholesterol levels, blood pressure, obesity, lack of physical activity and smoking. People aged 65 to 74 years are also made aware of the signs of dementia.

Between 2015 and 2020, 25.8% of eligible individuals in Devon had an NHS Health Check, compared to 38.9% in the Southwest and 41.3% in England. The checks are funded by public health and delivered by primary care with a test and learn outreach model. It is important that individuals take up the offer when invited and the number of checks could be improved but is limited in part by the budget available.

Even just a few years after an NHS Health Check, attendees can show better health outcomes, including lower levels of hospital admissions and death from heart attacks and strokes

Having a significantly lower uptake of NHS Health Checks compared to the rest of the Southwest and England, this represents a significant opportunity for improvement if investment is available.

Case Study: Outreach NHS Health Checks

Outreach health checks, targeted to populations less likely to seek an NHS health check in primary care are being piloted in Devon. Devon PH have partnered with the RDUH Vaccination Outreach Service to test the approach which builds on their learning from the Pandemic.

The aim of this work is to narrow health inequalities by improving access to the check which helps people understand their personal CVD risk profile, engage in conversations around what matters most to them and how to seek ongoing support if required.

Smoking cessation

Tobacco is the single biggest cause of preventable illness and death in England. Smoking causes around 25% of all UK cancer deaths, including the great majority of lung cancer, the UK’s most common cause of cancer deaths. It is also a major cause of premature heart disease, stroke and heart failure, and increases the risk of dementia. It underlies most chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), triggers severe asthma, and exacerbates many chronic diseases. Since smoking increases the risks for multiple diseases in one person, it increases multimorbidity and as such, measures taken to reduce or stop smoking completely are important strategies for ageing well. The latest (2022) data shows that the smoking rate in Devon is 13.9% which is higher than the English average of 12.7%.

From a health point of view, it is never too late to stop smoking with some of the effects on disability being felt rapidly. Quitting at any age increases life expectancy and reduces the risk of developing smoking-related diseases. There is evidence that older people are less likely to access stop smoking support services.

Targeted smoking cessation campaigns are rarely focused on older adults. Furthermore, the location and accessibility of services may also act as a barrier to older people.

Older people who smoke have often smoked for a long time and are therefore highly addicted, making it harder to quit. ‘Trigger events’ such as an episode of ill health can still result in attempts to quit, as can prompts from family and health professionals.

Given the high levels of contact that many older people have with health and social care services, there are likely to be regular and repeated opportunities to signpost to smoking cessation services.

Source: Photo by Ricardo Resende on Unsplash

Vaccination

Vaccination can help to prevent or reduce the severity of certain infections across the life course. Vaccination can benefit older adults directly, as receiving a vaccine will prime their immune response to future infections, or indirectly through vaccination of other population groups, for example through vaccination of children.

There are effective vaccines which are recommended for people aged 65+, such as vaccinations for influenza, pneumococcus, shingles and COVID-19, which make an important contribution to health and longevity, particularly to those in earlier old age. When examining vaccination uptake rates, it needs to be recognised that there is inequity in uptake with data showing for some programme uptake is lowest within the most deprived communities.

Screening

Cancer is a major cause of ill health and poor quality of life in older age. The likelihood of developing cancer increases with age, largely due to genetic changes within our cells accumulating over time. This damage can occur naturally or as a result of exposure to risk factors such as smoking, alcohol and obesity.

Cancer survival has improved significantly over recent decades, as a result of improvements in primary prevention measures, such as smoking rates and advances in diagnosis and treatment. Outcomes are better for cancers diagnosed and treated early and as such can reduce the burden of cancer in older age.

Identifying cancer early is an important way of reducing the impact of the disease on an individual’s quality of life. Early diagnosis can be achieved through the provision of screening programmes, which are an effective tool for preventing cancer mortality and morbidity. Screening enables cancer to be detected at an earlier stage, when cancers are smaller, less likely to have spread, and where treatment is therefore both less invasive and more likely to be successful.

Screening programmes are available for cervical, bowel and breast cancer, and a new targeted lung cancer screening programme has recently been announced. Additional national screening programmes that screen for other diseases are also available, including abdominal aortic aneurysm screening and diabetic eye screening.

However, screening rates are not uniform and variation in screening rates is apparent between population groups. Screening coverage is consistently lower in people from more deprived groups and in those with disabilities. There is evidence that people from ethnic minority groups are also less likely to attend screening but estimates vary by ethnic group and across different screening programmes. The impact of this on health in older age can be substantial. Uptake of screening programmes across the area should be monitored and evaluated by geography and by key population group, such as the CORE20PLUS groups. Barriers to uptake of screening programmes should be identified and addressed.

Source: Photo by Marek Studzinski on Unsplash

Oral health

Oral health is an important but often neglected area of health for older adults. Poor oral health may be the result of a person’s diet, but in turn can also affect nutrient intake and the variety of food consumed by older adults. Other risk factors associated with poor oral health include tobacco use, alcohol use, poorly controlled diabetes, stress and trauma. Oral disease can also contribute to cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, increase the risk of pneumonia and lead to social isolation.

Challenges in accessing NHS dental care can be a financial barrier for older adults, particularly for those who are less financially secure, increasing inequalities in oral care. Reducing oral health interventions requires a combination of universal interventions, such as reducing the content of sugar in diets, promoting better oral hygiene, access to fluoride products and access to dental care, alongside additional proportionate interventions for population groups at increased risk of poor oral health.

Professionals working across the health and social care sector can support good nutritional intake among older adults by being aware of the challenges that these individuals may experience and provide advice and practical support. Many older adults may be dependent on others for care, including oral care. Care home residents generally have poorer oral health than those living independently and face additional challenging in accessing the care to which they need. Oral health promotion and nutritional support within care homes can therefore help improve quality of life among residents. In Devon, our oral health improvement service delivers high quality mouth care training for care home staff and work to connect care home staff with dedicated NHS dental services.

Source: Photo by sk on Unsplash

Falls prevention

Falls and fall-related injuries are common in older adults, have negative effects on functional independence and quality of life, and are associated with increased morbidity, mortality and health and care related costs. There are clear inequalities when it comes to falls with the data showing those most deprived having a higher rate of emergency admission following a fall than the least deprived.

Preventing older adults from falling is a societal challenge that requires involvement from multiple sectors and organisations. Falls prevention includes medical, environmental, behavioural, and human factors, which impact across the NHS, social care, housing and the built environment and the voluntary and community sector.

Many falls can be prevented. Fall and injury prevention requires multidisciplinary assessment and management. Opportunistic case finding for falls risk is recommended for older adults living in the community. Those considered at high risk should be offered a comprehensive multifactorial falls risk assessment with a view to co-design and implement personalised multidomain interventions. All care home residents should be considered high risk and would benefit from a multifactorial falls risk assessment and tailored intervention strategy.

Clinicians should routinely ask about falls in their interactions with older adults, as they often will not be spontaneously reported, and asked about the frequency, context and characteristics of the fall. This is especially true for men, with less than a third mentioning them to their clinician if not asked directly. Engaging older adults is essential for prevention of falls and injuries: understanding their beliefs, attitudes and priorities about falls and their management is crucial to successfully intervening.

Two key health-related behaviours for the primary and secondary prevention of falls and non-vertebral fractures are maintaining adequate nutrition and physical activity, including aerobic, strength and balance. Other modifiable risk factors are high alcohol consumption and smoking (bone health). To be effective to prevent falls, programmes should comprise a minimum of 50 hours or more delivered for at least two hours per week. They should involve highly challenging balance training and progressive strength training. Managing many of the risk factors for falls have wider benefits including an improved quality of life.

Commissioners and providers should ensure that barriers to services are addressed. This includes raising awareness that falls are not an inevitable part of ageing and what older people can do to prevent them; encouraging uptake including establishing effective referral pathways; using a person-centred and evidence-based approach; and monitoring outcomes.

Steady On Your Feet is a campaign led by the NHS and local authorities delivered locally to help increase confidence and reduce the risk of falls as we age. The programme provides free access to advice, guidance and resources for anyone worried about feeling unsteady on their feet, together with information on strength and balance classes open to everyone in Devon by self-referral. They aim to equip people with simple tips to stay active, independent and safe during everyday activities.

Source: Photo by Craig Cameron on Unsplash

Environment

In addition to the direct preventative actions which can be undertaken to help prevent, delay or minimise disability and frailty the other key element to focus on it the environment, both the built and natural environment. The built environment can either promote people remaining healthy, active and living independently into older age, or indeed have a negative impact and reduce the likelihood of this happening.

Poor quality housing can contribute to the development and the exacerbation of long-term conditions and reduce the amount of time people are able to live independently. Within the CMO report it suggests that the nationally the NHS spends over £1 billion per year on treating people affected by poor quality housing.

As we see a rise in the concentration of older people in Devon within our rural and coastal towns, good infrastructure and good transport links are important to help people to stay in their own home as they age, still maintain social relationships, and access essential services.

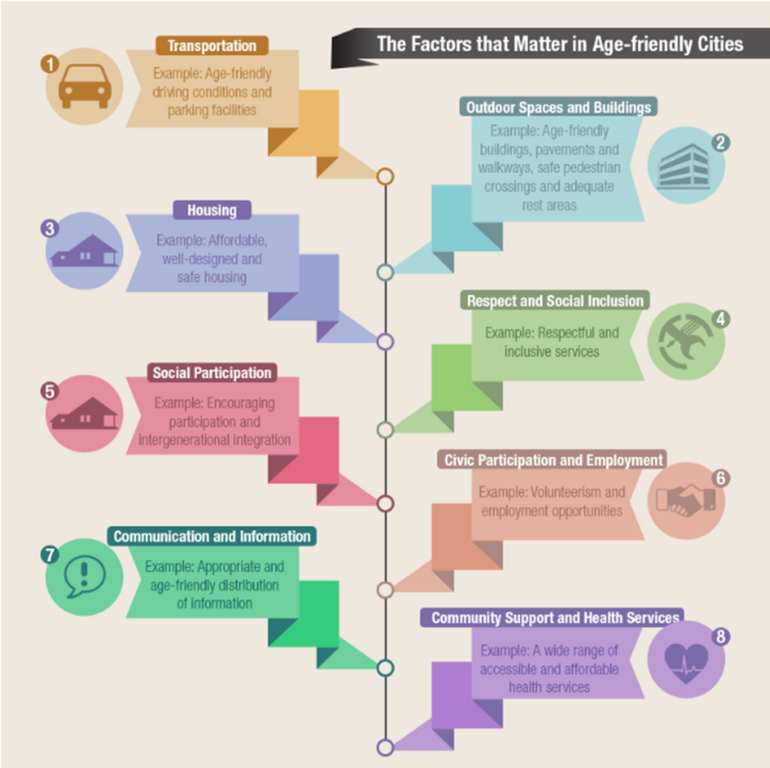

The World Health Organisation’s age-friendly communities framework shown in figure 3.10 has developed an eight-domain approach to the guide the development of age-friendly communities. The eight domains are the areas of the built and social environment which, when acted upon, can help to address barriers to ageing well: outdoor spaces and buildings; housing; transportation; social participation; respect and social inclusion; civic participation and employment; communication and information; and community support and health services.

Figure 3.10: World Health Organization’s age-friendly community eight domain approach

Source: World Health Organization, 2023

Implementing the framework in Devon could support inclusion and improve health and wellbeing and reduce health inequalities through a cross-sector approach. Figure 3.11 provides examples of things that matter in age-friendly communities and provide a framework for action.

Figure 3.11: The factors that matter in age-friendly communities

Source: World Health Organization, 2023

By becoming a World Health Organization affiliated age-friendly community, we can take important steps forward to ensure that Devon is a community in which the population can enjoy their later life in health and happiness.

Caring for our older carers and people with additional needs

We all age identically chronologically, however some people biologically age substantially faster than others. The inequality in the rate of biological ageing is affected by the social and economic environments in which people live and work and are largely preventable. For example, those who live in areas of economic and material deprivation experience greater exposure to risk factors, such as smoking and access to green space, compared to those living in the least deprived areas.

As risk factors cluster in communities, approaches may need to reflect this, ensuring collaborative system working and ensuring that the principle of proportionate universalism is applied. As described by the Marmot Review Fair Society, Healthy Lives this involves spreading resources across all communities to improve everyone’s health but with a scale and intensity proportionate to need, in order to close the life expectancy gap. Additional and specific consideration is required for minority and inclusion groups relevant to Devon to ensure that the proposed recommendations to ensure that Devon is a place where the population can age well equally.

Core20PLUS5 is a national NHS England approach to inform action to reduce healthcare inequalities at both national and system level. The approach defines a target population, the ‘Core20PLUS’, and identifies other vulnerable population groups where there may be isolation and small areas of high deprivation hidden amongst relative affluence.

The Devon Integrated Care Board (ICB) identifies a number of ‘plus’ groups for additional prioritisation. This includes, individuals, families and communities experiencing coastal or rural deprivation; individuals, families and communities adversely affected by differential exposure to the wider determinants of health, for example, those with unstable housing or homeless, vulnerable migrants and those experiencing domestic abuse; and persons with severe mental illness, learning disability and/or neurodiversity.

Source: Photo by Hannah Busing on Unsplash

The Southwest is a Marmot region so has access to experts in tackling health inequalities and can learn from other areas and take local action with colleagues to ensure all the population of Devon can have the opportunity to age well together.

Where possible, interventions should be co-produced with input from older adults and individuals from the identified inclusion groups, including older carers, to improve the likelihood of the intervention being successful and to ensure the interventions meet their needs. Given the geographical spread of the population of Devon, with pockets of geographical isolation and deprivation there must be equity of access to prevention activities, this should be monitored and evaluated.

Older carers represent an important, yet often unidentified and harder to reach group of individuals, who may have additional health and wellbeing needs owing to their role as a carer and will benefit from additional pro-active support. Minority groups, such as those from LGBTQ+ communities and ethnic minority groups, have been shown to be even less likely to identify themselves and be identified by health professionals as carers.

Older carers are often invisible, with many older carers providing long hours of vital care and support while their own health and wellbeing deteriorates, resulting in poor physical and mental health, financial strain, and breakdown in their ability to carry on caring. Carers’ health deteriorates incrementally with increased hours of caring and the oldest carers are more likely to spend more hours caring than those who are younger, particularly as this is compounded by the fact that age-related illness will be more likely.

With an ageing population and increasing demand on health and social care services, supporting older carers better is a key approach to keeping people at home, independent and healthy. Efforts to improve carer identification and referral for early support include the establishment of links between primary care and community services and local carers organisation is essential. Training should be established for health and care staff in carer awareness and the importance of carer identification, and to establish referral pathways with local carers organisations. This can help ensure that health and care staff not only identify carers but link them to a range of local support. Joint work with local voluntary groups is important to ensure that there is support for people from different parts of the community to reach carers from diverse backgrounds, including targeted work to reach and support marginalised carers.

Living well with disease

While the aim is to reduce the amount of time people spend in poor health as we age it is increasingly likely that we will gradually accumulate medical conditions. Therefore, it is important that we consider how people are supported to live well with multiple long-term conditions. This does require the health and care system to work together to ensure that key prevention interventions for example falls prevention programmes, housing adaptations, community alarms, reablement, the use of technology enabled care and support are available to help people live independently for as long as possible. The Integrated Adult Social Care team in Devon County Council has produced an Ageing Well strategy Ageing well – Promoting independence which describes a number of actions and programmes to enable people to live independent, healthy and active lives for as long as possible.

Reflections

When you review the evidence, the high impact actions which promote healthy ageing and thus help prevent, delay or minimise disability and frailty fall into two broad categories. Firstly, it is about prevention. This includes actions such as stopping smoking, being physically active to help with our physical and mental health, ensuring you have social interaction. It also includes attending screening programmes, ensuring you take up vaccinations you are eligible for and early diagnosis and intervention of conditions such as high blood pressure and dementia. Much of this is personal responsibility but we know due to inequalities not everyone has the same opportunities or choice, so it is important that the prevention actions while offered universally are targeted at those in greatest need.

The second key element is the environment we live in. This clearly does include a prevention element as we know air pollution and living in poor quality, cold, damp homes increase your risk of disease but also impacts on your mental health. Where you live, the proximity of services, opportunity, including people with disability, to access social and cultural activities play a significant role in people living well and independently. As we see a rise in the number of older people in Devon and an increase in people living with long-term conditions, disease and disability there is a need to ensure that we use this knowledge and plan accordingly.

To support people to remain independent there is a need to scale up the work on prevention, focus on the highest concentrated areas of older people and on creating communities which are age-friendly to help people age well and live independently for as long as possible. It is also clear that those living in the most deprived communities within Devon suffer greatest, not only is their live expectancy lower than those living in the least deprived areas, but the number of years they spend in poor health is also greater. It is therefore vital that when we consider prevention and environmental actions these are proportionately targeted at the most disadvantaged communities to tackle health inequalities.

Recommendations

3. Increase targeted action on promoting people staying active physically, mentally and socially.

4. Explore the adoption of Devon as a World Health Organization Age friendly community.

5. Deliver on the Smoke-free generation ambitions and scale up our offer to support more smokers to quit.

6. Work with key partners to increase action on the early identification and intervention of key health conditions, including high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, dementia, people at risk of falls.

7. Support the national epidemiological survey on oral health in people aged 65yrs+ in care homes.

8. Maintaining high attendance at national screening and uptake of national immunisation programmes.

9. Equality impact assessments should be undertaken on all policy decisions to ensure that proposed actions are proportionately targeted at the most deprived communities to tackle health inequalities.

4. Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA)

The Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) looks at the current and future health and care needs of the local population and it is a legal requirement of the Health and Wellbeing Board to produce and publish a JSNA. The assessment informs and guides the planning, commissioning and delivery of local health, wellbeing and care services. For more detailed JSNA information, data and intelligence, please visit Joint Strategic Needs Assessment – Devon Health and Wellbeing.

Devon is the third largest county in the country with beautiful natural environment and history attracting many residents and tourists to live and visit the area. Devon has great potential in providing individuals and families with the opportunity to live a healthy and fulfilled life. Like many areas, there are challenges which exist for Devon residents which can impact upon this ability to live a healthy life.

Population

Devon has a growing and ageing population, with proportionately more older people compared to the England average. The growth of the Devon population is influenced by longer life expectancy, internal migration and increases in new developments across the country. Currently the population of Devon is around 225,000, with older people (65+) accounting for around 26.7% of the total population. By 2043, we expect this to rise to 32.1%. Annually there are around an additional 8,000 people that come to Devon when we take into account internal and external migration (47,000 coming into the county and 39,000 exiting the county). Life expectancy across Devon on average is around 85 years for men and 87 years for women.

Inequalities

Health and wellbeing outcomes are influenced by the conditions in society – where people are born, grow, live, work and age. Differences in health and wellbeing outcomes arise because of differences in society. These differences are referred to as inequalities in health and wellbeing. While across England we do not observe the extreme inequalities seen globally, inequality is still substantial and tackling these factors remains a priority.

Across Devon, people living in the poorer neighbourhoods tend to, on average, die between 5 and 7 years earlier that people living in more affluent neighbourhoods. However, the difference in life expectancy is even more stark in smaller areas such as Central Ilfracombe and Liverton in Exmouth where there is a staggering 15-year difference. Moreover, people in poorer areas also spend more of their shorter lives with a disability and/or in poorer heath.

Health and Wellbeing

In Devon, the leading causes of life lost to ill health, disability or early death for all ages include cancer, cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders, respiratory infections and neurological disorders. Similar to other areas and countries, COVID-19 has influenced the positioning of respiratory infections in the latest data release. Cancer, cardiovascular diseases and musculoskeletal disorders have remained unchanged in their positioning of ranking over the past 15 years.

Prevention

The upstream downstream metaphor is a useful way to illustrate what we mean by prevention. With a broken bridge, many people fall into the river. The further they drift downstream, the more support and treatment they may require as poorer health manifests downstream. However, by repairing the bridge, this can prevent people falling into the water in the first place.

Across Devon, leading risk factors that influence life lost to ill health, disability or early death are dominated by behaviour risk factors followed by metabolic and then environmental risk factors according to the Global Burden of Disease (2021).

Behavioural risk factors remain leading risk factors to poorer health and proportionately is higher in younger age groups. What is interesting is as we move through the life course, the impact of behavioural risk factors on metabolic risk factors becomes undoubtedly apparent and this proportionately starts to increase particularly from the ages of 50 years and over. What we are seeing is the downstream impact of behavioural risk factors on working age and older age groups.

While longer life expectancy has been influenced by technological advances together with better detection and treatment of ill health, for the first time in 100 years we have seen little change in life expectancy more recently. As such, more prevention work is required to improve the conditions in where people are born, grow, live, work and age to improve health and wellbeing outcomes for the population of Devon.

For more detailed information around JSNA and JSNA dashboards, please visit Joint Strategic Needs Assessment – Devon Health and Wellbeing

5. Recommendations 2022-23 Update

| Recommendations 2022-23 | Update on Progress |

| Devon Integrated Care Partnership should work together to realise the potential they have as anchor institutions to improve the lives of local people and reduce health inequalities, drawing on evidence of the impact of this approach from other areas. | The Devon Integrated Care Partnership anchor institution steering group is now well established. It meets regularly to share actions taken in progressing an anchor institution approach within our respective organisations. The Civic University Agreement (CUA), between DCC and the University of Exeter, is an important driver of this approach within the County Council and is now linked into the ICS anchor institution steering group. The CUA has three priorities (Employment, Housing and Children and young people). The ICS steering group has identified employment as the first system wide priority. Local Care Partnerships (LCP), notably the Eastern LCP, are also levering improvements in health and equity through taking an ‘anchors’ approach. Public Health contribute to the SW Regional Anchor Institution Network, run by OHID, to share with and learn from other areas and have also benefitted from the ‘Marmot Region’ focus on employment and health. |

| Devon Health and Wellbeing Board to consider the impact of the climate emergency on health and equity, through the production of a joint strategic needs assessment; The board should review, adopt and monitor the partnership’s climate change mitigation and adaptation plans and the opportunities they present to create a fairer, healthier, more resilient and more prosperous society. | Public Health Devon, NHS Devon and the Devon Climate Emergency partnership coordinator jointly presented the case for a Joint Strategic Needs Assessment to help the H&WB consider and mitigate the impacts of the climate and ecological emergency on health and equity. The H&WB agreed that the impact of the climate emergency on health and equity should be considered within the JSNA and any future Devon Health and Wellbeing Strategy. The Board also wished to review, adopt and promote action, and monitor progress on climate change mitigation and adaptation plans. The key plans are the Devon Carbon Plan, the Devon, Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Climate Adaptation Strategy, and the Greener NHS plans. They noted that all these plans present opportunities to create a fairer, healthier, more resilient and more prosperous society. They also agreed to sign the Devon Climate Emergency Declaration. |

| Public Health Devon to actively work with system partners to support the delivery of the agreed Joint Forward Plan (JFP) objectives and actions in relation to taking the wider determinants of health. | The health protection section of the Joint Forward Plan (JFP) has been updated and refreshed and has been approved by system colleagues. The new condensed version of the JFP was submitted to to the NHS Devon Board and will ensure health protection remains a priority within the JFP. The next step is reporting progress on the plan and the deliverables through the operational group. |

| Public Health Devon to actively participate in the Marmot Region work programme and ensure learning is shared with Integrated Care Partnership. | The SW Marmot region developments are shared through the system with learning and network opportunities. |

| The Devon Food Partnership and the Energy Saving Devon partnership utilise every opportunity to address health, equity and the climate emergency through their collective programmes. | Energy Saving Devon and the Devon Food Partnership supports and promotes approaches – through conducting research and developing policies and programmes – that minimise harmful environmental impacts whilst maximising positive health and equity outcomes for communities. A qualitative Study on ‘The Face of Food Insecurity in Devon’ was produced, which together with previous survey research, is informing how the partnership can best support those facing chronic food insecurity, whilst also reducing food waste and improving access to nutritious, local, sustainably produced food. Energy Saving Devon is working to ‘make every house in Devon regenerative, healthy to live in and affordable to run’. The partnership runs an advice line to help ensure that people in most need are sign-posted to grants they may be eligible for and to get support from their local community energy organisation. In addition, the partnership has shared learning from social prescribing, fuel poverty pilot projects. These projects have addressed health, equity and climate change issues in one by linking patients, in areas of deprivation, who are at risk of an exacerbation of their health condition from cold and damp housing with advisors in community energy organisations who can provide support, advice and access to home improvement grants and benefits. |

| Public Health Devon and Devon Integrated Care Partnership to work collaboratively with communities within multi-agency alliances, to develop and refine multi-level programmes of action on the leading modifiable risk behaviours (tobacco, food, excess weight, alcohol, physical inactivity), ensuring there is an appropriate mix of individual and population level approaches to make an impact at pace and scale. | Multi-agency programmes of action on the leading modifiable risk behaviours in Devon are working towards a balance of activities to support behaviour change at individual level but also create more supportive conditions at community and environmental level. Tobacco The Smokefree Devon Alliance works closely with the NHS Devon led Treating Tobacco Dependence programme to ensure broader tobacco control elements, including creating supportive strategy and policy and tackling illicit tobacco products, supports action at an individual level to reduce the smoking prevalence in the county. A new programme of grant funded activity to support a Smoke Free Generation will work to scale up individual quits attempts but also to support System-wide action to reinforce a smoke free culture, in communities where smoking rates remain stubbornly high. Smoke Free Generation funding was also awarded to support enforcement agencies such as trading standards, Border Force and HMRC to implement and enforce the law and tackle illicit trade. Food The Devon Food Partnership seeks to take a broad view of food within a system, following the six key themes of Sustain’s Sustainable Food Places. This approach aims to create action which considers food activities within this broader perspective, which in turn improves the conditions to support individual based services and action to improve diets in Devon. There are specific focuses currently within the Partnership’s sub-groups on reducing Food Insecurity in Devon and improving the School Food environment. Excess weight Public Health Devon has helped transform the ICB Devon Healthy Weight group into a Health and Weight Strategic Learning Group which is a supportive and collaborative space to address this complex issue. The group is focussing currently on children, young people and families and focuses on both individual behavioural change support and change to the conditions that drive unhealthy weights. In the last year One Devon commissioned the Innovation Unit to develop Healthy Devon Learning Labs, promoting healthy lives and bodies through whole system collaboration and person-centred care and support. Public Health Devon was part of the core steering group developing the programme which included ethnographic research to highlight perspectives across lived and professional experience, mapping interdependencies across Devon and a Devon wide conference to share learning and mobilise energy. Grant funding has been used to test and learn innovative approaches. A framework and action plan for Devon, outlining a compassionate systems approach which seeks to strike a balance between individual level support and broader conditions which make healthier weights easier for all, has been developed. Alcohol The Devon Alcohol Harm Reduction (AHR) Group seeks to ensure local alcohol partnerships and systems are effective in preventing and reducing alcohol-related harm. The AHR group encompasses a broad stakeholder and partnership membership, to consider approaches and action in the context of prevention & early intervention, treatment & support for those who are dependent on alcohol including those living with multiple challenges, and promoting trauma informed approaches. Physical inactivity Public Health Devon works internally with teams across Devon County Council, and alongside key partners to promote increased physical activity across the population, supporting work to facilitate healthy environments and remove barriers for people to become more active in our communities. Work includes collaborative partnerships with the Active Travel Team, to support and advise on the health benefits of infrastructure investment projects in local communities, as well as working with districts to support place-based initiatives. A new partnership, Tackling Health Inequalities through Physical Activity (THIPA) has just formed to focus on helping everyone in Northern Devon to have the opportunity to live an active life – especially those who could benefit most. Public Health Devon is part of this group, to support identifying opportunities for collaboration and aligning resources. |

| Public Health Devon to work with stakeholders in Devon Integrated Care Partnership to develop and implement a programme of professional development to upskill the workforce in compassionate, health gains approaches to healthier weight to destigmatise individual behavioural change interventions, promoting confidence and emotional wellbeing. | Work continues to develop around implementing a more compassionate approach to healthier weight in Devon and reducing weight stigma across the system. This includes working collaboratively with NHS colleagues supporting people experiencing eating disorders and disordered eating behaviours to align messaging and approaches, with a particular focus on prevention in children and young people through working with schools. Specifically, this includes promoting a holistic view of wellbeing and a curriculum that is reflective of the current evidence base, as well as supporting schools with their whole school approach and their school environment in relation to food, movement, and emotional health and wellbeing. This aligns with the work of the Devon Schools Wellbeing Partnership, where a commitment has been made to fund training on Body Image for school staff, forming part of a broader offer provided to schools by the ICB and the Mental Health Support Teams.Public Health Devon are part of the Devon Health and Weight Strategic Learning Group, a collaborative group of colleagues from Devon, Plymouth, and Torbay local authority areas and NHS trusts. Discussions are ongoing on how to effectively implement an aligned training offer for the workforce across the whole of the area, that raises awareness of weight stigma broadly, and also meets the needs of professionals and organisations who are in contact with and/or supporting people with their health and wellbeing. The Devon group are also linked into regional collaborative work to align messaging and workforce development approaches in this space. |

| Public Health Devon to work with system partners to test place-based approaches to drive community-based prevention action. These should be designed with and informed by local communities, utilise community assets and act on clustered risks, utilising proxy measures to demonstrate impact in the short to medium term. | Community Action Groups (CAG) Devon has previously supported local community groups working on Climate action. Public Health Devon funded research to establish whether communities and partner organisations saw any need for an expansion of this support: geographically across the county, and through an expansion of the remit of CAG from a focus on reducing waste to wider environmental goals such as sustainable transport and improving equity of access to nature and renewable energy. The research demonstrated the widespread support across the system for building community capacity to take action on climate change and that such action was intrinsically linked to the development of healthier and more resilient communities. Public Health Devon is now supporting an expanded CAG programme the aim of which is to create and support a network of engaged community groups that are helping their communities become healthier, more resilient, net-zero communities.Through the Food Insecurity sub-group of the Devon Food Partnership, a proposal to support place-based projects which increase access to nutritious and affordable food for local communities is developing. This project has been designed to respond to evidence generated by recent local research, to build capacity of local communities to provide different food club models which suit local need and provide a contribution to addressing the endemic nature of food insecurity. This place-based approach, which is needs-led and embedded in a community capacity building approach, takes time to develop, but will provide learning around long-term, sustainable approaches which start with a focus on food insecurity, but has the potential to connect in other health improvement activities which address multiple elements important for wellbeing, including the wider determinants of health. Communities will co-produce and agree the outcome framework which will feature impact measures demonstrating change in what matters most to them. This project recognises the potential for this activity to take place as part of the family hubs model, so will be seeking opportunities to embed this approach as the model develops. |

| Through the Population Health Management programme, the Devon Integrated Care System should implement a range of data-based approaches for case finding for avoidable conditions or to improve outcomes. These methods should focus on detecting the precursors and early stages of disease, design preventive interventions and monitor their impact. | The Devon Population Health Management programme has continued to mature in terms of data-based approaches for case finding with a prevention and early intervention focus. The One Devon Dataset, the local linked dataset combining primary care, secondary care, social care, mental health and wider health determinant information at an individual and population level is an important mechanism for this. One Devon Dataset use cases approved during 2023-24 relating to case finding and early identification of preventable and amenable conditions included Dementia coding (to improve recording by aligning service data), primary care data extracts for Public Health services, hypertension optimisation, the prediction of stroke, and hospital admission risk stratification. Other use cases relating to prevention and Public Health include fuel poverty and health risk stratification, waiting list inequalities and the health and wellbeing of care-experienced young people. Work on these use cases will contribute to targeted preventive action. Work is also underway to develop a Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Inequalities dashboard, combining information on access to services and outcomes relating to CVD and exploring inequalities to assist in the targeting of services. |

| Following the success of the Devon mass vaccination inequalities cell through the Covid-19 pandemic, the application of a multi-disciplinary inequalities cell approach to secondary prevention programmes to drive action around community engagement and targeting and reducing inequalities | Building on the learning from vaccination outreach in Covid, the Royal Devon University Hospital Trust vaccination outreach team have been contracted by Public Health Devon to test a new targeted delivery model for NHS Health Checks and are delivering checks in communities where there is limited access through our primary care contract or to improve access for groups who are not well served by the core offer. The RDUH Team are trusted faces in the places they are visiting, building on the foundations of trust built during the pandemic. They are working closely with other trusted community leaders (trusted faces in trusted places) to make to the checks welcoming, informative and easy for key target populations to access, as part of our programme of activities targeting and reducing health inequalities. |

| There should be equity in access to services and all levels of preventative support including screening and vaccination, with proactive community engagement and reasonable adjustments where needed building on learning from outreach work during the pandemic | The model for vaccination outreach and engagement has continued for the cohort that remain eligible for vaccination and the learning is being applied to wider programmes delivered through the Maximising Immunisation Uptake group.The system wide Population Health Steering group maintains a focus on inclusion health and access. |